For those unfamiliar with the controversial 1991 fictional novel written by Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho is a satirical look at 1980’s yuppie New York (or more accurately Wall Street), and centers around the exploits of wall street executive, Patrick Bateman (played expertly in the film adaption by Christian Bale) who also happens to be a narcissistic sociopath. I’ve read the book a couple of times, and whilst I certainly respect its sharpness and Ellis’s bold pull no punches approach to some of the more violent passages, the overly vulgar rhetoric and profanity littered throughout ultimately feels like overkill. With hindsight, Writer/Director, Mary Harron (I Shot Andy Warhol) certainly proved the right person to be entrusted with its transition from script to screen, comprehensively elevating the essence of the material whilst simultaneously maintaining the prevalent ambiguity within the novel. I’ve watched the film countless times and analyzed it to the hilt. I find the characters compelling, the situations fascinating and hilarious, and the material layered. So much so, that with each viewing I gain something new, or an alternative insight into any one of its scenes. There’s something that has irked me ever since its release all the way back in April of the year 2000 (if you don’t mind), and that’s that you’d walk into any local video store to find American Psycho squarely positioned on the top shelf of the “Horror” section – that always bothered me, and here’s why.

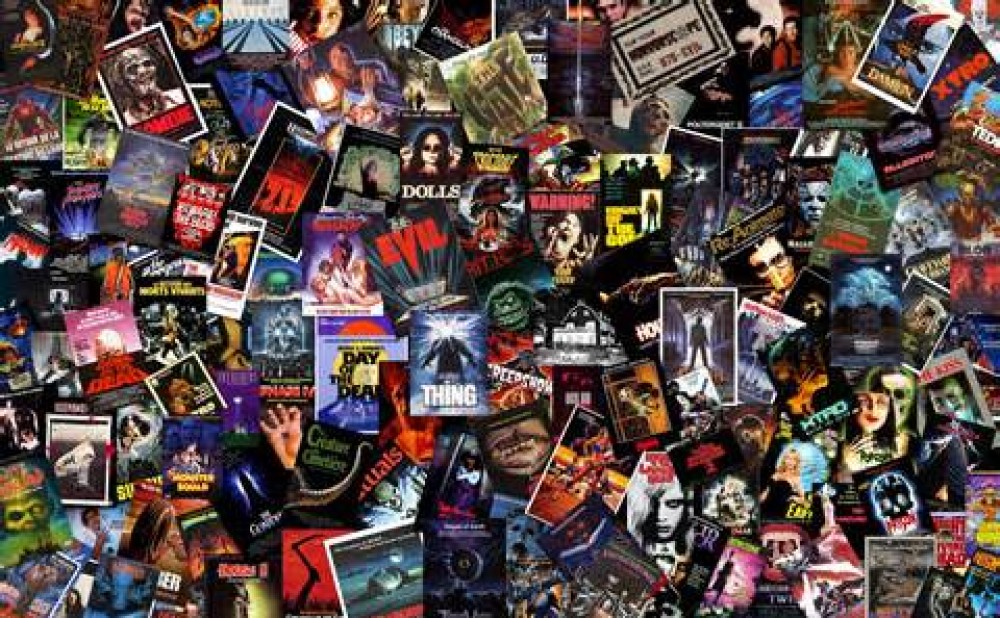

Not only are both the book and film almost entirely satirical in nature, the underlining psychological component (complete with first person narration and all) makes it a far more cerebral foray than anything else you’d ever find in the run-of-the-mill horror section of a Blockbuster. Now, that’s not to say violent acts aren’t committed on screen throughout the duration of the film… or are they? I suppose it depends on your perspective. There’s evidence to track the support of both arguments though, and hell, Bale is even depicted on the poster art holding a Michael Myers style kitchen knife, right? I’ve always felt that image did the film more harm than good – misleading people and inadvertently lotting the film in with a bunch of the straight to video B-movie titles. I don’t know, maybe it’s just me and I’m reading too much into it, but there’s something about American Psycho sitting on the same shelf as John Carpenter’s iconic 1978 slasher film “Halloween” that rubs me the wrong way (and yet I love both films). So for those looking for a little more method to the madness, I thought I’d discuss some of the finer points and key themes present in the film, what it all means, and perhaps quantify why American Psycho is most deserving of its own metaphorical shelf.

MISTAKEN IDENTITY

At the top of the list is undoubtedly the recurring theme of mistaken identity, something ever present throughout American Psycho. It’s perhaps the biggest staple of the film. On display from the opening dinner scene, all the way up to one of the iconic closing sequences in Harry’s Bar. From the outset, Ellis highlights the carbon copy nature of these individuals (and I use that term “individual” loosely) who inhabit Wall Street and its far-reaching climate, and continues to then validate that lack of individualism both through imagery and dialogue. Shortly into the runtime, we’re officially introduced to one of those so-called individuals, Pat Bateman – our protagonist (in the sense that we sit with him for the entirety of the film) who almost immediately reveals himself to be an unreliable narrator. Thus setting in motion the dilemma of reality vs fantasy, a talking point that will inevitably be raised by the viewer as the film unfolds. With the sheer number of times mistaken identity comes into play, is it any wonder no one knows what’s real and what’s not – including Patrick. Here’s a breakdown of those central occurrences.

- In the opening scene, Bryce and McDermott (co-workers of Patrick’s) make reference of Paul Allen (who is eventually revealed to be played by Jared Leto) sitting at the table across from them. Bateman corrects them, or so he thinks, directing their attention to another man who looks like everyone else in the restaurant who he believes to be Allen – it’s not.

- The second example is in the boardroom where Paul Allen is actually the one guilty of mistaking Bateman for another co-worker, Marcus Halberstram. Bateman proceeds to divulge to the viewer that the two do the same exact job, own similar suits, glasses, and even go to the same barber (although Patrick has a slightly better haircut if you ask him). This is the first time the audience witnesses that pattern of mistaken identity developing and that perhaps Bateman isn’t the only one doing it. In the same scene, Paul asks Patrick (or Marcus according to him) about Cecilia – someone we don’t know, and also refers to McDermott as “Baxter”. The only central female we’ve been introduced to up until this point is Evelyn (Reese Witherspoon) who is Patrick’s supposed fiance. Patrick plays along with Allen’s false small talk, though the reason for that remains a mystery.

- At the work christmas party, Hamilton (another colleague) greets Patrick as “McCloy” and despite Evelyn approaching and calling Patrick by his name, Hamilton doesn’t appear to notice. At the same party, Paul runs into Patrick (referring to him as Marcus again) and suggests they have dinner, and that he bring his girlfriend Cecilia along (who is not Patrick’s girlfriend). Important to note that Paul hesitates, searching for a name to come to him when it’s Bateman that eventually interjects with Cecilia’s name. When questioned by Evelyn about why Paul called Patrick “Marcus”, he simply signals the mistletoe and ignores her. At this point Evelyn appears to be the only person who correctly identifies those around her.

- Patrick checks in at Texarkana for dinner with Paul Allen under the guise of Marcus Halberstram. Whilst name dropping someone at a table opposite them, Patrick accidentally utters his own name under his breath – quickly correcting it. However, Allen doesn’t seem to notice.

- When Detective Donald Kimball (played by Willem Dafoe) enters proceedings he makes mention of someone he interviewed and how they mistook another colleague for Paul Allen.

- In a frenzied state, Patrick call his lawyer and in the start of the call refers to him as “Howard” (which we later learn is actually Harold).

- In the closing stages of the film, Bateman’s aforementioned lawyer “Harold Carnes” refers to him as “Davis” and asks him how “Cynthia” is.

INDIVIDUALISM AND SOCIAL STATUS

Whilst mistaken identity is by and large the key element troubling not only Bateman, but all the characters that occupy this yuppie landscape, the core underpinning is the absence of anything resembling an identity – inevitably resulting in confusion among the suits. By the same token, socio-economic status becomes the primary currency with which these traders deal in. If you don’t get reservations at the best eateries, you don’t live in the right part of Manhattan, and your business card doesn’t scream “Look at me”, you risk your reputation and ultimately how others may or may not perceive you. Bateman tells you exactly who or what he is (or more accurately isn’t) right off the bat, and his hollow vapid nature is on display for the remainder of the film.

There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman; some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me: only an entity, something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze, and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable… I simply am not there.

Upon first viewing, most people are unlikely to give Patrick’s opening monologue a second thought, but what he’s doing is letting you know there’s a self-awareness within. That perhaps he isn’t actually a character in the true sense of the word, on the contrary, the culmination of the worst traits and behaviors of that society in that place and time – a walking cliché. Let’s talk about Bateman’s need for validation at every turn and his desire to constantly profess something (anything) of worth to his peers. And how in pursuit of that, he reveals himself to be not only a hypocrite but vain, and in addition, a compulsive liar.

The Do’s and Don’ts Of Wearing A Bold Striped Shirt

First, Bateman wears his narcissism loudly and proudly, evident from the moment he begins filling us in on his daily morning routine of which involves yoga, stomach crunches (a thousand of them to be precise), showering, and a level of skin care application that would likely put any woman’s to shame. Patrick sees an opportunity during early narration to name drop the address of his Upper West side apartment as if we, the audience, actually care. The need for social status affirmation is actually first exhibited in the opening dinner scene when McDermott asks why the group aren’t eating at Dorsia (an establishment we later learn is seemingly impossible to get a reservation at) and from there, the men proceed to whip out their American Express cards dismissively to pay for a dinner that cost $570. The attitudes of these individuals are summed up by David Van Patten’s line in the last scene at Harry’s Bar “I mean I’m not really hungry but I’d like to have reservations somewhere”. Money is no objection for the elite and they’ll use it anytime they’re in a jam. Bryce can be seen giving extra cash to the door guard at the nightclub for preferential treatment, and later, Patrick even makes a cheque out to Christie in order to appease her hesitations about another night with him.

I’m on the verge of tears by the time we arrive at Espace, since I’m positive we won’t have a decent table. But we do, and relief washes over me in an awesome wave.

Below are just a handful of examples where Patrick flexes his social status.

- He makes damn sure the dry cleaner knows his sheets are expensive and that they’re from Santa Fe.

- He name drops both Donald Trump and Ivana Trump.

- Patrick has a moment of sheer panic when he realizes Paul’s apartment overlooks the park and is clearly more expensive than his.

- He mentions a carry bag being made by Jean Paul Gaultier.

- He later requests that an escort not wear the “Bijan” bathrobe.

There Are A Lot More Important Problems Than Sri Lanka To Worry About.

Christian Bale’s depiction of Bateman is incredible. All the little nuances in facial expressions and the beats between lines perfectly convey all the characters insecurities. There’s nothing that matters more to Bateman than status and the desire to be the envy of all others. So on the rare occasions that he doesn’t get the response he wants, there’s nowhere for him to maneuver.

I’m leaving. I’ve assessed the situation, and I’m going.

The options are either remove himself from the situation altogether, or alternatively, he’s forced to sit and stew. As is depicted perfectly in the scene where in a very matter of fact way, he asks Christie and Sabrina (the two escorts) if they want to know what he does for a living – to which they answer no. Seeing this as yet another attempt to big-note himself, Patrick tells them he works on Wall Street at Pierce and Pierce and asks them if they’ve heard of it – to which they both shake their heads from side to side. Needless to say, his contempt for them in that moment is palpable and simply articulated through one effortless scowl. Such bizarre actions and reactions to seemingly trivial things such as a place of employment, is what makes the film so darkly funny. Later, Patrick makes random wisecracks about the irony of Ted Bundy’s dog being called “Lassie”, to which his secretary Jean asks, “Who’s Ted Bundy?” and another to co-workers about 1950’s serial killer, Ed Gein (who they think is the maître d’ of Canal bar).

The most important aspect to remember about Bateman is how desperately he needs the approval of his peers (and in turn the audience) and for them to believe how educated and worldly he is. Of course none of these opinions he gives are actually his own. They’re always delivered methodically and are quite clearly a collection of well rehearsed tidbits that he’s either read somewhere or inevitably picked up through the evolution of pop culture.

Evelyn Williams: You hate that job anyway. I don’t see why you just don’t quit.

Patrick Bateman: Because I want to fit in.

Let’s talk about how time and time again Patrick contradicts himself, despite what he might have you think.

During their dinner at Espace, Bryce raises the question of massacres in Sri Lanka and how that might affect them, to which Patrick declares that there’s bigger problems to concern themselves with.

Well, we have to end apartheid for one. And slow down the nuclear arms race, stop terrorism and world hunger. We have to provide food and shelter for the homeless, and oppose racial discrimination and promote civil rights, while also promoting equal rights for women. We have to encourage a return to traditional moral values. Most importantly, we have to promote general social concern and less materialism in young people.

After giving what sounds a hell of a lot like political campaign hyperbole, Bryce does what most of us would do and mockingly chuckles at Bateman. Luis, however, gives Patrick some highly sought-after validation – with a response of “How thought-provoking”. It all sounds well and good in theory, but Patrick’s simply echoing the thoughts of the masses. Ironically, when he’s actually presented with the opportunity to provide either food or shelter for the homeless, not only does he not do so, he proceeds to mock and eventually kill the poor vagrant. By the same token, you wouldn’t find a group of more chauvinistic and immoral men than the ones Patrick surrounds himself with – and certainly none are worse than him. Bateman constantly critiques and objectifies the women in his life, and never once seems remotely interested in their thoughts or opinions. Here are a few examples of responses he gives throughout the film.

- “Don’t wear that outfit again, wear a dress, a skirt or something”.

- “I’m trying to listen to the new Robert Palmer tape, but Evelyn, my supposed fiancée, keeps buzzing in my ear”.

- “You should take some more lithium or have a Diet Coke, some caffeine might get you out of this slump”.

- “You’re not quite blonde, more dirty blonde”.

- “There are no girls with good personalities”.

- “You’re not terribly important to me”.

- “If you really want to do something for me, then stop making this scene right now”.

With hindsight, you can laugh the hardiest at Bateman’s notion of promoting less materialism in young people given all that transpires. It’s a statement that proves to be the pinnacle of hypocrisy once you break down the sheer volume of over indulgence and excessiveness in the film.

This Is Sussudio, A Great, Great Song, A Personal Favorite.

Music is a big part of American Psycho, and in particular Patrick’s life. There’s a number of great 80’s songs throughout, but three specific artists feature in pivotal scenes throughout the film, Huey Lewis And The News, Phil Collins, and Whitney Houston. The first of which happens after Bateman and Allen have dinner and return to the former’s apartment for drinks. It’s unclear whether Bateman’s almost album review like monologue of Huey Lewis and The News is purely for distraction, or just another opportunity to educate a fellow associate. Either way, it’s painfully phoney and very funny.

Their early work was a little too new wave for my tastes, but when Sports came out in ’83, I think they really came into their own, commercially and artistically. The whole album has a clear, crisp sound, and a new sheen of consummate professionalism that really gives the songs a big boost. He’s been compared to Elvis Costello, but I think Huey has a far more bitter, cynical sense of humor.

Later in the film, Bateman gives another two pompous, long-winded album critiques on both the aforementioned Phil Collins and Whitney Houston. It becomes quickly apparent that he doesn’t have an original thought about much of anything. For all his perceived enthusiasm, when Detective Kimball reveals that he just purchased the very same Huey Lewis And The News album, Bateman resorts to complete fabrication.

Donald Kimball: Huey Lewis and the News. Great stuff! I just bought it on my way here. You heard it?

Patrick Bateman: Never. I mean I don’t really like singers.

Donald Kimball: Not a big music fan, huh?

Patrick Bateman: No, I like music. Just they’re… Huey’s too black sounding for me.

For almost its entire runtime, Patrick is giving you a running commentary on anything and everything, and yet the most fascinating thing about him as a character is that when the film finally comes full circle and he’s finally asked to give his personal opinion on something (for perhaps the first time) as pertinent as the Iran-Contra controversy, he simply answers Bryce with “Whatever.” Almost as if he’s finally accepted the fact that it really doesn’t matter what he thinks because no one’s listening and no one cares.

Timothy Bryce: He makes himself out to be a harmless old codger, but inside… inside…

Patrick Bateman: [voice-over] … “but inside” doesn’t matter.

Craig McDermott: “Inside,” yes, “inside… ” – believe it or not, Bryce, we’re actually listening to you…

Timothy Bryce: Come on, Bateman, what do you think?

Patrick Bateman: Whatever.

I Was Probably Returning Video Tapes

Lies come thick and heavy from the mouth of Patrick Bateman. Some big, some small, but undeniably present at every corner. The genius quality around the idea of an unreliable narrator is that perhaps they aren’t all lies, and maybe it’s just that we don’t see every interaction, hear every conversation, or are ever even officially introduced to all the characters who are spoken about. Why Patrick lies remains somewhat of a mystery. Although if I had to wager a guess, I’d say it’s equal parts self-preservation as well as morbid curiosity surrounding the response, and in turn what his next move would be in a chess game where he’s the only player. Below showcases the potential extent of his lies.

- He tells Jean he’s late because of Aerobics class, yet later we see that he does his workouts from home.

- Patrick also tells Jean he boxes with a Ricky Harrison at the Harvard Club, who knows whether there’s any truth to that one.

- Evelyn makes reference to Patrick’s father practically owning the company. There’s never any mention of his father or evidence to him owning anything. Perhaps it’s a lie Patrick is just facilitating.

- Patrick says he’s got a lunch date at Hubert’s in fifteen minutes and ignores Victoria when she questions whether it moved uptown or not. He then prompts plans with her for the next Saturday and when she moves to agree, tells her he’s got a showing of Les Mis.

- He tells Courtney they’re at Dorsia when they’re actually at Arcadia (as shown on the menu) and then lies to Luis about getting a reservation at Dorsia.

- Patrick continues to let Paul Allen believe that his girlfriend is named Cecilia.

- He pretends to be having a phone conversation with a John and then divulges on the supposed specifics of the fictional conversation to Detective Kimball.

- In reference to Paul Allen he says “I think for one that he was probably a closeted homosexual who did a lot of cocaine”.

- Patrick tells Kimball he has a lunch meeting with Cliff Huxtable at the Four Seasons (Cliff Huxtable is a fictional character from The Cosby Show).

- Patrick starts referring to himself as Paul Allen.

- Patrick constantly uses returning video tapes as an excuse to get out of any given situation.

- “Kimball I’ve been wanting to talk with you” – yeah, that’s a lie.

- Kimball questions Bateman about the last time he saw Paul Allen, to which he responds with “We’d gone to a new musical called Oh, Africa, Brave Africa it was a laugh riot, that was about it”. You can see Patrick workshopping this lie as he’s telling it.

- Patrick lies about having not heard Huey Lewis And The News. How does he know it’s “too black sounding” if he hasn’t heard it.

- He lies to Jean about having made a reservation for them at Dorsia.

- He hilariously stumbles around telling Jean that he isn’t really seeing anyone (despite supposedly being engaged to Evelyn).

- Claims to want a meaningful relationship with someone special.

- During a lunch meeting with Kimball, Patrick says on the night of Paul’s disappearance he only had a shower and some sorbet.

- Patrick tells Elizabeth that Christie is his cousin and that she’s from France – both of which we know are lies.

- Elizabeth asks Patrick if he knows the guy who disappeared from Pierce and Pierce and he says no. The man is Paul Allen. Although if you accept that no one knows each other in a literal sense, maybe it’s not a lie.

REALITY VS FANTASY

The chief topic of conversation surrounding American Psycho is the notion of reality vs fantasy, and how much, if any, of what we see throughout the film can actually be believed. Is it happening as we see it? Or is it simply visual representation of fantasy stemming from Bateman’s sick and depraved imagination? As soon as you accept that Bateman is an unreliable narrator, the quicker you’ll discover evidence to be found for both arguments. Let’s analyze the signs both for and against, and we can begin that by first looking at various things Patrick says that either go unheard or unnoticed, and then we can look at the remaining visual instances.

You’re My Lawyer, So I Think You Should Know I’ve Killed A Lot Of People

The first example comes early in proceedings when Patrick insults and threatens a bartender. I suppose it could simply be that the venue has dance music blaring at full volume and with her back to him she can’t see or hear him speaking. But all the same, maybe it’s what he really wanted to say and just didn’t.

You’re a fucking ugly bitch. I want to stab you to death, and then play around with your blood.

The second time it happens is when Patrick is attempting to get his sheets dry cleaned. He tells the Chinese woman that if she doesn’t shut her mouth, he’ll kill her. This tracks a little clearer, if for no other reason than she doesn’t speak English so therefore she wouldn’t even know that he was threatening her with physical violence – it doesn’t mean he did though…

During a dinner with Paul Allen, Patrick boasts that he’s “utterly insane and likes to dissect girls”. He conveniently discloses this while Paul is substantially inebriated, leaving it open to interpretation as to whether Bateman ever said it at all or Paul ignored it or didn’t hear it because he’s too drunk.

Similar to the first example, in a later nightclub scene Bateman tells a model he meets that he’s into “murders and executions”. Only this time she does hear him, but mistakenly thinks he says “mergers and acquisitions”. Once again, it’s a loud environment so who knows how it’s really delivered, if at all.

The last one is from an interaction Patrick has with Evelyn during a luncheon. She seems more pre-occupied with eyeing someone she knows across the room (who is donning new jewelry) than actually listening to what he’s got to say. It further supports the commentary on her (and everyone else) being so materialistic and the lack of care.

Patrick Bateman: I think, um, Evelyn that, uh, we’ve lost touch.

Evelyn Williams: Why? What’s wrong?

Patrick Bateman: My need to engage in homicidal behavior on a massive scale cannot be corrected but, uh, I have no other way to fulfill my needs.

There are certainly moments that seem so outlandish that you can almost surely chalk them up to delusion though. Most of these emerge in the final act and I’ll get into those in more detail shortly, but here’s a brief list of other instances that raise the debate of reality and fantasy.

- Patrick is childishly laughed at on the phone while trying to make a booking at Dorsia. I’m not sure you’d ever find someone react in that fashion, but hey, this is the upper echelon of 1980’s, New York – so who knows?

- Patrick appears to leave a clear blood trail behind in the lift lobby while dragging a body. There’s a guard at the entrance that doesn’t notice.

- Patrick fills in a crossword with only the words “meat” and “bone”. This little detail could be down to what he’s got running through his mind though.

- Patrick plans to use a nail gun, but it’s one that clearly requires a compressor to run and therefore he wouldn’t be able to fire it.

- Patrick runs through an apartment building in the middle of the night with a live chainsaw (surely someone would notice?)

- He then drops the chainsaw from great heights and accurately hits a moving target. This would seem highly unlikely. Firstly, that it would spin correctly, and secondly, land perfectly on the woman as well.

- Christie runs screaming and banging door to door and yet no one answers. Creating such a disturbance (combined with said chainsaw) would surely alert those in the building and curiosity would likely get the better of at least one tenant, right?

This Confession Has Meant Nothing

Things begin to unravel quickly from the moment of complete randomness involving a roaming cat appearing at Bateman’s feet, followed by an ATM message requesting that he feed it a stray cat… (yeah that one is most definitely where we enter a state of hallucinatory perplexity). In the same motion, Patrick shoots a lady and then is forced to evade police. Everything that follows is fortuitously carried out in entirely empty streets, and in New York that just simply isn’t reality (irrespective of the time of day). Hello! it’s one of the most populated cities in the world. And if that weren’t enough to highlight how far down the rabbit hole we’ve come, witnessing Patrick defy all logic and blow up multiple cop cars with a handgun should suffice. There’s a genius touch in Bale’s acting throughout the scene, where he oddly marvels at what’s transpired and moves to check his watch (as if to signal that the night is still young). From there, he swiftly kills a security guard in one building (and spares another in hilarious fashion) as well as a cleaner on his way to another building. Bateman turns on a dime, frenzied to paranoid, so much so that he gets confused trying to locate the building he works in. Once inside, he hides under the desk out of the line of sight of a circling helicopter – (lights are shown moving around accompanied by propeller sounds). Personally, I go back and forth with each viewing on whether the helicopter is ever really present, or if it’s just a further manifestation of his paranoia which is now amped up to eleven. What follows is perhaps the most powerful scene in the film, in which Patrick makes a call to his lawyer Harold Carnes (addressing him as Howard instead). Unfortunately, he gets the answering machine and decides to leave a detailed recorded confession, topped off with the important revelation that he killed Paul Allen (with an axe to the face).

One could easily be excused for only seeing things in one light, at least up until the vital scene that follows where Patrick returns to the scene of the crime. That scene being Paul Allen’s superior apartment, the crime being the murders of multiple women. It takes Bateman a minute to realize that the very same apartment he was just in has now been cleaned, freshly painted (all white) and apparently put on the market (as is evident by the woman giving a couple a tour). You know how real estate works in NY I guess! Patrick opens the closet where the bodies of two young woman wrapped in plastic had previously hung, only to find commercial painting gear. Furthermore, the adjacent room once stained with blood soaked walls and body parts strewn about it now looks a million dollars (in excess, if I know my property market). The most common automatic response from viewers upon this unveiling is that everything was probably just in his head – hold that thought and keep reading.

Patrick is accosted by the upper crust looking agent and questions her about it being Paul Allen’s place. He asks her if Paul lives there, to which she says no (but how would she know?). She prompts Patrick in return, mentioning if he saw the ad for the apartment in the Times, a comment that ultimately catches him in a lie. She seems leery their entire interaction and promptly requests he leave and that he not make any trouble. It’s important to note that she never mentions calling the authorities if he refuses though. I wonder why that might be? Could it be that in a world inhabited by so many people intent on material gains, a life built on consumerism, that an individual might have seen the perfect opportunity to profit from the misfortune of others? I don’t think it’s that big of a stretch to imagine the woman (who may own other tenancies in the building already) stumbling across a grisly crime scene and seeing it for the prime piece of real estate it is, an avenue with which to make a sizeable profit from. She likely could have paid a few people off, gotten a clean up crew, had multiple coats of fresh paint applied, and placed it on the market all the while knowing something horrible happened there. What are the chances the person responsible returns to the scene of the crime? The odds would likely be slim to none, so why not? After all, every investment is part gamble isn’t it? Did the woman gamble and seize an opportunity? Or did Patrick only imagine killing these women?

This Is Not An Exit

We’ve now arrived at the culmination of American Psycho and the scene inside Harry’s Bar between Bateman and Harold Carnes (his lawyer). With all his dirty laundry aired out (and it’s as dirty as it comes), Patrick confronts Carnes to find out if he got his message, and the response he’s met with is less than ideal. It seems Harold has interpreted the confession as a practical joke, something clearly commonplace among colleagues in the business. Carnes confuses Patrick for a Davis and goes on to tell him how it was an amusing joke but his fatal flaw was making Bateman the butt of the joke instead of Bryce or McDermott. Patrick reiterates that he is Bateman, and that the two talk on the phone all the time, questioning why Carnes doesn’t recognize him. Could it be that he’s not actually Patrick’s lawyer despite the fact Patrick thinks he is? Frustrated and angry, he continues to stress that he is in fact Bateman and not Davis and that the whole message he left on the answering machine was true.

I did it, Carnes. I killed him. *I’m* Patrick Bateman. I chopped Allen’s fucking head off.

In the end, it all falls on deaf ears as Carnes tells Bateman that he couldn’t possibly have killed Paul Allen because the two had dinner in London multiple times just ten days earlier. In that very instant, it’s clear that even Patrick (who has been popping pills) doesn’t know up from down anymore or exactly where the lines of reality and fantasy may very well blur. This final scene is another in which the viewer tends to fall on the side of the argument of “it’s all in his head”. Whilst that may very well be the case, it could also mean that perhaps the man Bateman believed to be Paul Allen wasn’t him after all. In fact, not once in any scene Jared Leto appears in (who is credited as Paul Allen) does he actually refer to himself as Paul Allen – it’s only something others do. Perhaps much in the same way Patrick does when someone calls him Marcus, Paul just rolls with the name regardless. And given what we know about mistaken identity and everyone being guilty of it, Who knows who Patrick actually killed? If anyone? He wants so desperately to be vindicated for all that he believes he’s done, yet fails to find anyone who will either listen or care. When all is said and done, it doesn’t matter what we, the audience, believe and more to the point, what Bateman believes. You can’t confess to something when no one’s accusing you of anything.

There are no more barriers to cross. All I have in common with the uncontrollable and the insane, the vicious and the evil, all the mayhem I have caused and my utter indifference toward it I have now surpassed. My pain is constant and sharp, and I do not hope for a better world for anyone. In fact, I want my pain to be inflicted on others. I want no one to escape. But even after admitting this, there is no catharsis; my punishment continues to elude me, and I gain no deeper knowledge of myself. No new knowledge can be extracted from my telling. This confession has meant nothing.

To use a couple of Bateman’s words, American Psycho is deep and enriching. It’s layered themes and complex subconscious make it endlessly re-watchable. I find the balance between the horror and satire of the material unparalleled. The cast are phenomenal, the direction is artful, and the messaging is strong – both for the good and the bad. American Psycho is a rare breed in a genre unto its own, and a film worthy of constant deconstruction and continued debate as we fast approach its 25th anniversary.